By Philip Stephens :Published: October 25 2007

George W.Bush warns that Iran’s nuclear ambitions threaten world war three. Vice-president Dick Cheney speaks of “serious consequences” unless Tehran falls into line. Joe Lieberman, the independent Democrat, says we are already fighting world war four against Islamist radicalism. As someone in the Hollywood movie said, it is time for the rest of us to be afraid, very afraid.

Afraid, though, of what? Of Tehran’s nuclear programme? Or of the possibility that Mr Bush, in the darkening twilight of his presidency, is preparing to launch a preventative military strike. The answer is both.

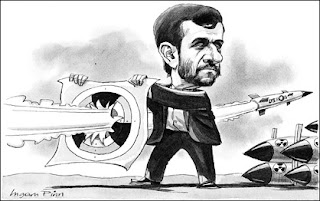

The big story, you might think, should be the menace to regional and global security posed by Iran’s development of the technology that would give it nuclear weapons. This, after all, is not a nice regime. You do not have to be an apologist for Washington to note that Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad, the Iranian president, has spoken of wiping Israel from the face of the globe. Nor to notice Tehran’s unapologetic sponsorship of terrorism. The regime’s human rights record is the wrong side of appalling.

Yet the White House once again seems hell-bent on being outwitted in the court of global opinion; and, maybe, on making a strategic miscalculation that could make the war in Iraq look like a sideshow.

Speculation about a US-backed Israeli or a direct American attack on Iran’s nuclear installations has ebbed and flowed for several years. In the immediate aftermath of the toppling of Saddam Hussein, “Iran next” was the stock refrain of the Washington hawks. The bellicose rhetoric was stilled for a time by Iraq’s descent into chaos. But it has never gone away, even as some of the most ardent advocates of another war in the Middle East have left the administration. Only the other day I heard John Bolton, the former US ambassador to the United Nations, say he was sure that Mr Bush would do “the right thing”.

The rising tempo of speculation is easily explained. The starting point is the political timetable. If Mr Bush does intend to act, he has to do so soon. The window of opportunity for an attack, the conventional wisdom has it, will close next summer. Even this president cannot take the nation into another war of choice once the 2008 election campaign is under way.

This ticking political clock coincides with a hardening view in Washington, and in one or two European capitals, that coercive diplomacy has done nothing to shake Iran’s resolve to acquire the means to make the bomb.

The apparent demotion of Ali Larijani as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator seems to speak to the same conclusion. Mr Larijani has been as firm as any in Tehran about Iran’s right to pursue nuclear enrichment, but he has also been willing to talk. Mr Ahmadi-Nejad, we might conclude, means it when he says the nuclear dossier is closed.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin’s objections to further UN sanctions has likewise strengthened the hand of those who say that diplomacy has run its course. Earlier this year Iran outflanked the so-called European Union 3 – Britain, France and Germany – by opening direct talks with the International Atomic Energy Agency. Now Mr Putin is blocking another UN resolution.

Nervousness about US intentions, meanwhile, has been heightened by speculation that Mr Bush could treat Iran’s support for Shia militias in Iraq as a casus belli. A senate motion ,co-sponsored by Mr Lieberman, calls for the Revolutionary Guards to be designated a terrorist organisation. That could provide the president with the political cover to bomb training camps within Iran.

The calculation, if you could call it that, would be that such attacks would destabilise Mr Ahmadi-Nejad and, in the best case, see him toppled. Logic suggests the reverse: an upsurge of nationalist sentiment would bolster support for the regime. For some people, though, logic does not count.

The thing I find most striking in conversations with western officials is simply how little is known about Iran: about the power balance within the regime, the dynamics of the nuclear programme and, critically, how far that programme has progressed.

A little while ago I heard one such official discuss the state of knowledge gleaned by various intelligence agencies. The Israelis thought Tehran was two years from acquiring the bomb; but they had been saying two years for as long as this official could remember. The Russians suggested that Iran was as much as a decade away from mastery of all the necessary technology. As for the US and the big European agencies, three to six years seemed to be a rough consensus. In other words, the spooks, once again, are being forced to make judgments while wearing blindfolds.

There is a similar lacuna of understanding of the political power balance. Take Mr Larijani’s troubles. Do they signal that Mr Ahmadi-Nejad has won a struggle with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, over control of the nuclear dossier? Or has a visible backlash against the move – it now seems Mr Larijani will keep a place in the Iranian nuclear delegation – delineated the limits of Mr Ahmadi-Nejad’s authority?

Diplomacy has not yet been exhausted. Russia’s position is more subtle than it sounds. For all the pleasure he takes in discomfiting the US, Mr Putin has more to fear from a nuclear-armed Iran. In any event, the US decision to leave it to the EU3 to do all the talking with Tehran has ensured that real negotiations have never properly started.

The US has yet to play its highest card: an offer, comparable to that made to, and accepted by, North Korea, of a comprehensive refashioning of the strategic relationship between the US and Iran. Unless and until that bargain is explored, it will never be clear whether Tehran could be persuaded to eschew the nuclear course.

Mr Bush is not alone in framing a simple choice between Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons and war. Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, has said much the same. It is a false choice. Even putting aside the chaos that would ensue from Tehran’s certain retaliation against any attack, the likely consequence of such thinking is war and a nuclear-armed Iran.

Last month, at a conference hosted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Washington office, one of those present recalled being taught by Henry Kissinger at Harvard. China had just tested the bomb and a fellow student suggested that the answer was a pre-emptive strike against its nuclear installations. And just how frequently should the US repeat the exercise? Mr Kissinger asked in response. Mr Bush might ask himself the same question.

No comments:

Post a Comment